Designing our Complex Future with Machines

While I had long been planning to write a manifesto against the technological singularity and launch it into the conversational sphere for public reaction and comment, an invitation earlier this year from John Brockman to read and discuss The Human Use of Human Beings by Norbert Wiener with him and his illustrious group of thinkers as part of an ongoing collaborative book project contributed to the thoughts contained herein.

The essay below is now phase 1 of an experimental, open publishing project in partnership with the MIT Press. In phase 2, a new version of the essay enriched and informed by input from open commentary will be published online, along with essay length contributions by others inspired by the seed essay, as a new issue of the Journal of Design and Science. In phase 3, a revised and edited selection of these contributions will be published as a print book by the MIT Press.

Version 1.0

Cross-posted from the Journal of Design and Science where a number of essays have been written in response and where competition winning peer-reviewed essays will be compiled into a book to be published by MIT Press.

Nature's ecosystem provides us with an elegant example of a complex adaptive system where myriad "currencies" interact and respond to feedback systems that enable both flourishing and regulation. This collaborative model-rather than a model of exponential financial growth or the Singularity, which promises the transcendence of our current human condition through advances in technology--should provide the paradigm for our approach to artificial intelligence. More than 60 years ago, MIT mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener warned us that "when human atoms are knit into an organization in which they are used, not in their full right as responsible human beings, but as cogs and levers and rods, it matters little that their raw material is flesh and blood." We should heed Wiener's warning.

INTRODUCTION: THE CANCER OF CURRENCY

As the sun beats down on Earth, photosynthesis converts water, carbon dioxide and the sun's energy into oxygen and glucose. Photosynthesis is one of the many chemical and biological processes that transforms one form of matter and energy into another. These molecules then get metabolized by other biological and chemical processes into yet other molecules. Scientists often call these molecules "currencies" because they represent a form of power that is transferred between cells or processes to mutual benefit--"traded," in effect. The biggest difference between these and financial currencies is that there is no "master currency" or "currency exchange." Rather, each currency can only be used by certain processes, and the "market" of these currencies drives the dynamics that are "life."

As certain currencies became abundant as an output of a successful process or organism, other organisms evolved to take that output and convert it into something else. Over billions of years, this is how the Earth's ecosystem has evolved, creating vast systems of metabolic pathways and forming highly complex self-regulating systems that, for example, stabilize our body temperatures or the temperature of the Earth, despite continuous fluctuations and changes among the individual elements at every scale--from micro to macro. The output of one process becomes the input of another. Ultimately, everything interconnects.

We live in a civilization in which the primary currencies are money and power--where more often than not, the goal is to accumulate both at the expense of society at large. This is a very simple and fragile system compared to the Earth's ecosystems, where myriads of "currencies" are exchanged among processes to create hugely complex systems of inputs and outputs with feedback systems that adapt and regulate stocks, flows, and connections.

Unfortunately, our current human civilization does not have the built-in resilience of our environment, and the paradigms that set our goals and drive the evolution of society today have set us on a dangerous course which the mathematician Norbert Wiener warned us about decades ago. The paradigm of a single master currency has driven many corporations and institutions to lose sight of their original missions. Values and complexity are focused more and more on prioritizing exponential financial growth, led by for-profit corporate entities that have gained autonomy, rights, power, and nearly unregulated societal influence. The behavior of these entities are akin to cancers. Healthy cells regulate their growth and respond to their surroundings, even eliminating themselves if they wander into an organ where they don't belong. Cancerous cells, on the other hand, optimize for unconstrained growth and spread with disregard to their function or context.

THE WHIP THAT LASHES US

The idea that we exist for the sake of progress, and that progress requires unconstrained and exponential growth, is the whip that lashes us. Modern companies are the natural product of this paradigm in a free-market capitalist system. Norbert Wiener called corporations "machines of flesh and blood" and automation "machines of metal." The new species of Silicon Valley mega companies--the machines of bits--are developed and run in great part by people who believe in a new religion, Singularity. This new religion is not a fundamental change in the paradigm, but rather the natural evolution of the worship of exponential growth applied to modern computation and science. The asymptote of the exponential growth of computational power is artificial intelligence.

The notion of Singularity--that AI will supercede humans with its exponential growth, and that everything we have done until now and are currently doing is insignificant--is a religion created by people who have the experience of using computation to solve problems heretofore considered impossibly complex for machines. They have found a perfect partner in digital computation--a knowable, controllable, system of thinking and creating that is rapidly increasing in its ability to harness and process complexity, bestowing wealth and power on those who have mastered it. In Silicon Valley, the combination of groupthink and the financial success of this cult of technology has created a positive feedback system that has very little capacity for regulating through negative feedback. While they would resist having their beliefs compared to a religion and would argue that their ideas are science- and evidence-based, those who embrace Singularity engage in quite a bit of arm waving and make leaps of faith based more on trajectories than ground-truths to achieve their ultimate vision.

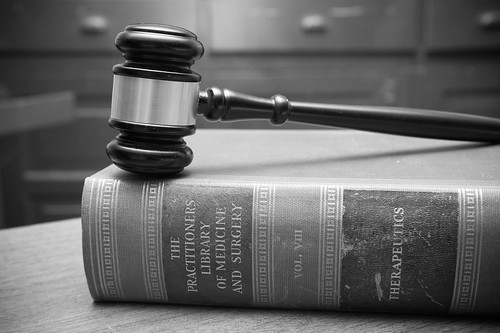

Singularitarians believe that the world is "knowable" and computationally simulatable, and that computers will be able to process the messiness of the real world just like they have every other problem that everyone said couldn't be solved by computers. To them, this wonderful tool, the computer, has worked so well for everything so far that it must continue to work for every challenge we throw at it, until we have transcended known limitations and ultimately achieve some sort of reality escape velocity. Artificial intelligence is already displacing humans in driving cars, diagnosing cancers, and researching court documents. The idea is that AI will continue this progress and eventually merge with human brains and become an all-seeing, all-powerful, super-intelligence. For true believers, computers will augment and extend our thoughts into a kind of "amortality." (Part of Singularity is a fight for "amortality," the idea that while one may still die and not be immortal, the death is not the result of the grim reaper of aging.)

But if corporations are a precursor to our transcendance, the Singularitarian view that with more computing and bio-hacking we will somehow solve all of the world's problems or that the Singularity will solve us seems hopelessly naive. As we dream of the day when we have enhanced brains and amortality and can think big, long thoughts, corporations already have a kind of "amortality." They persist as long as they are solvent and they are more than a sum of their parts--arguably an amortal super-intelligence.

More computation does not makes us more "intelligent," only more computationally powerful.

For Singularity to have a positive outcome requires a belief that, given enough power, the system will somehow figure out how to regulate itself. The final outcome would be so complex that while we humans couldn't understand it now, "it" would understand and "solve" itself. Some believe in something that looks a bit like the former Soviet Union's master planning but with full information and unlimited power. Others have a more sophisticated view of a distributed system, but at some level, all Singularitarians believe that with enough power and control, the world is "tamable." Not all who believe in Singularity worship it as a positive transcendence bringing immortality and abundance, but they do believe that a judgment day is coming when all curves go vertical.

Whether you are on an S-curve or a bell curve, the beginning of the slope looks a lot like an exponential curve. An exponential curve to systems dynamics people shows self-reinforcement, i.e., a positive feedback curve without limits. Maybe this is what excites Singularitarians and scares systems people. Most people outside the singularity bubble believe in S-curves, namely that nature adapts and self-regulates and that even pandemics will run their course. Pandemics may cause an extinction event, but growth will slow and things will adapt. They may not be in the same state, and a phase change could occur, but the notion of Singularity--especially as some sort of savior or judgment day that will allow us to transcend the messy, mortal suffering of our human existence--is fundamentally a flawed one.

This sort of reductionist thinking isn't new. When BF Skinner discovered the principle of reinforcement and was able to describe it, we designed education around his theories. Learning scientists know now that behaviorist approaches only work for a narrow range of learning, but many schools continue to rely on drill and practice. Take, as another example, the eugenics movement, which greatly and incorrectly over-simplified the role of genetics in society. This movement helped fuel the Nazi genocide by providing a reductionist scientific view that we could "fix humanity" by manually pushing natural selection. The echoes of the horrors of eugenics exist today, making almost any research trying to link genetics with things like intelligence taboo.

We should learn from our history of applying over-reductionist science to society and try to, as Wiener says, "cease to kiss the whip that lashes us." While it is one of the key drivers of science--to elegantly explain the complex and reduce confusion to understanding--we must also remember what Albert Einstein said, "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler."1 We need to embrace the unknowability--the irreducibility--of the real world that artists, biologists and those who work in the messy world of liberal arts and humanities are familiar with.

WE ARE ALL PARTICIPANTS

The Cold War era, when Wiener was writing The Human Use of Human Beings, was a time defined by the rapid expansion of capitalism and consumerism, the beginning of the space race, and the coming of age of computation. It was a time when it was easier to believe that systems could be controlled from the outside, and that many of the world's problems would be solved through science and engineering.

The cybernetics that Wiener primarily described during that period were concerned with feedback systems that can be controlled or regulated from an objective perspective. This so-called first-order cybernetics assumed that the scientist as the observer can understand what is going on, therefore enabling the engineer to design systems based on observation or insight from the scientist.

Today, it is much more obvious that most of our problems--climate change, poverty, obesity and chronic disease, or modern terrorism--cannot be solved simply with more resources and greater control. That is because they are the result of complex adaptive systems that are often the result of the tools used to solve problems in the past, such as endlessly increasing productivity and attempts to control things. This is where second-order cybernetics comes into play--the cybernetics of self-adaptive complex systems, where the observer is also part of the system itself. As Kevin Slavin says in Design as Participation, "You're Not Stuck In Traffic--You Are Traffic."3

In order to effectively respond to the significant scientific challenges of our times, I believe we must view the world as many interconnected, complex, self-adaptive systems across scales and dimensions that are unknowable and largely inseparable from the observer and the designer. In other words, we are participants in multiple evolutionary systems with different fitness landscapes4 at different scales, from our microbes to our individual identities to society and our species. Individuals themselves are systems composed of systems of systems, such as the cells in our bodies that behave more like system-level designers than we do.

While Wiener does discuss biological evolution and the evolution of language, he doesn't explore the idea of harnessing evolutionary dynamics for science. Biological evolution of individual species (genetic evolution) has been driven by reproduction and survival, instilling in us goals and yearnings to procreate and grow. That system continually evolves to regulate growth, increase diversity and complexity, and enhance its own resilience, adaptability, and sustainability.5 As designers with growing awareness of these broader systems, we have goals and methodologies defined by the evolutionary and environmental inputs from our biological and societal contexts. But machines with emergent intelligence have discernibly different goals and methodologies. As we introduce machines into the system, they will not only augment individual humans, but they will also--and more importantly--augment complex systems as a whole.

Here is where the problematic formulation of "artificial intelligence" becomes evident, as it suggests forms, goals and methods that stand outside of interaction with other complex adaptive systems. Instead of thinking about machine intelligence in terms of humans vs. machines, we should consider the system that integrates humans and machines--not artificial intelligence, but extended intelligence. Instead of trying to control or design or even understand systems, it is more important to design systems that participate as responsible, aware and robust elements of even more complex systems. And we must question and adapt our own purpose and sensibilities as designers and components of the system for a much more humble approach: Humility over Control.

We could call it "participant design"--design of systems as and by participants--that is more akin to the increase of a flourishing function, where flourishing is a measure of vigor and health rather than scale or power. We can measure the ability for systems to adapt creatively, as well as their resilience and their ability to use resources in an interesting way.

Better interventions are less about solving or optimizing and more about developing a sensibility appropriate to the environment and the time. In this way they are more like music than an algorithm. Music is about a sensibility or "taste" with many elements coming together into a kind of emergent order. Instrumentation can nudge or cause the system to adapt or move in an unpredictable and unprogrammed manner, while still making sense and holding together. Using music itself as an intervention is not a new idea; in 1707, Andrew Fletcher, a Scottish writer and politician, said, "Let me make the songs of a nation, I care not who makes its laws."

If writing songs instead of laws feels frivolous, remember that songs typically last longer than laws, have played key roles in various hard and soft revolutions and end up being transmitted person-to-person along with the values they carry. It's not about music or code. It's about trying to affect change by operating at the level songs do. This is articulated by Donella Meadows, among others, in her book Thinking in Systems.

Meadows, in her essay Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System, describes how we can intervene in a complex, self-adaptive system. For her, interventions that involve changing parameters or even changing the rules are not nearly as powerful or as fundamental as changes in a system's goals and paradigms.

When Wiener discussed our worship of progress, he said:

Those who uphold the idea of progress as an ethical principle regard this unlimited and quasi-spontaneous process of change as a Good Thing, and as the basis on which they guarantee to future generations a Heaven on Earth. It is possible to believe in progress as a fact without believing in progress as an ethical principle; but in the catechism of many Americans, the one goes with the other.6

Instead of discussing "sustainability" as something to be "solved" in the context of a world where bigger is still better and more than enough is NOT too much, perhaps we should examine the values and the currencies of the fitness functions7 and consider whether they are suitable and appropriate for the systems in which we participate.

CONCLUSION: A CULTURE OF FLOURISHING

Developing a sensibility and a culture of flourishing, and embracing a diverse array of measures of "success" depend less on the accumulation of power and resources and more on diversity and the richness of experience. This is the paradigm shift that we need. This will provide us with a wealth of technological and cultural patterns to draw from to create a highly adaptable society. This diversity also allows the elements of the system to feed each other without the exploitation and extraction ethos created by a monoculture with a single currency. It is likely that this new culture will spread as music, fashion, spirituality or other forms of art.

As a native Japanese, I am heartened by a group of junior high school students I spoke to there recently who, when I challenged them about what they thought we should do about the environment, asked questions about the meaning of happiness and the role of humans in nature. I am likewise heartened to see many of my students at the MIT Media Lab and in the Principles of Awareness class that I co-teach with the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi using a variety of metrics (currencies) to measure their success and meaning and grappling directly with the complexity of finding one's place in our complex world.

This is brilliant, sophisticated, timely. Question, what do you want to do with this manifesto? Socio-economic political cultural movement? To begin with, who do you want to read this? In what spaces?I know people who are working on this on the political side. I am interested in the arts and sciences ie buildable memory cultural side.

Don't know if people would agree with my conclusions here, but I've been working on developing my music in relation to housing issues around the Bay Area recently.I believe that it's important for us to develop a sensibility for diversity not just as an abstract exercise, but in ways that reflect our day to day lives. We're in need of new visions of how we plan to co-exist with one another, and I do think that artists have the ability to pave the way here in very real ways.

I'm also heartened by organizations such as the IEEE, which is initiating design guidelines for the development of artificial intelligence around human wellbeing instead of around economic impact. The work by Peter Seligman, Christopher Filardi, and Margarita Mora from Conservation International is creative and exciting because it approaches conservation by supporting the flourishing of indigenous people--not undermining it. Another heartening example is that of the Shinto priests at Ise Shrine, who have been planting and rebuilding the shrine every twenty years for the last 1300 years in celebration of the renewal and the cyclical quality of nature.

In the 1960s and 70s, the hippie movement tried to pull together a "whole earth" movement, but then the world swung back toward the consumer and consumption culture of today. I hope and believe that a new awakening will happen and that a new sensibility will cause a nonlinear change in our behavior through a cultural transformation. While we can and should continue to work at every layer of the system to create a more resilient world, I believe the cultural layer is the layer with the most potential for a fundamental correction away from the self-destructive path that we are currently on. I think that it will yet again be about the music and the arts of the young people reflecting and amplifying a new sensibility: a turn away from greed to a world where "more than enough is too much," and we can flourish in harmony with Nature rather than through the control of it.

1. An asymptote is a line that continually approaches a given curve but does not meet it at any finite distance. In singularity, this is the vertical line that occurs when the exponential growth curve a vertical line. There are more arguments about where this asymptote is among believers than about whether it is actually coming.

2. This is a common paraphrase. What Einstein actually said was, "It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience."

3. Western philosophy and science is "dualistic" as opposed to the more "Eastern" non-dualistic approach. A whole essay could be written about this but the idea of a subject/object or a designer/designee is partially linked to the notion of self in Western philosophy and religion.

4. Fitness landscapes arise when you assign a fitness value for every genotype. The genotypes are arranged in a high dimensional sequence space. The fitness landscape is a function on that sequence space. In evolutionary dynamics, a biological population moves over a fitness landscape driven by mutation, selection and random drift. (Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary Dynamics: Exploring the Equations of Life. Harvard University Press, 2006.)

5. Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary Dynamics: Exploring the Equations of Life. Harvard University Press, 2006.

6. Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings (1954 edition), p.42.

7. A fitness function is a function that is used to summarize, as a measure of merit, how close a solution is to a particular aim. It is used to describe and design evolutionary systems.

Credits

Review, research and editing team: Catherine Ahearn, Chia Evers, Natalie Saltiel, Andre Uhl

![Joi Ito [logo]](/_site/img/joi-ito-logo-300.png)